Intel’s Transformation Continues

Intel’s stock has sold off in the last few days despite reporting top- and bottom-line beats for the fourth quarter because the company lowered its guidance for the first quarter of 2024.

Intel’s stock has sold off in the last few days despite reporting top- and bottom-line beats for the fourth quarter because the company lowered its guidance for the first quarter of 2024. Intel said that it expects revenue in the first quarter to be between $12.2B and $13.2B (compared to $14.25B estimate) and expects EPS of $0.13/share (estimate was $0.42/share). This cautious guidance caused the stock to drop nearly 12% on Friday. Intel attributed the softer guidance to poorer performance across its business lines with notable inventory corrections in its Mobileye and FPGA (Field Programmable Gate Arrays) segments. After quarters like this, it is helpful to review our long-term bullish thesis for the companies we own and make sure they are still intact.

We own Intel for essentially three reasons: (1) its growing Revolutionary foundry business; (2) its Revolutionary process leadership roadmap; and (3) its Revolutionary AI potential. We will discuss each in turn and provide our “sum of the parts” valuation for Intel at the end of the article.

Intel Foundry Services (IFS)

Let’s look first at the foundry business (that is, the business of manufacturing chips for “fabless” chipmakers like NVIDIA (NVDA)). Intel’s plan to become one of the largest third-party foundries in the world is on track (and perhaps even ahead of schedule, despite continued universal doubt), and the company continues to sign new foundry customers every quarter. As a reminder, currently, only Taiwan Semiconductor (TSMC), Samsung, and Intel can manufacture advanced semiconductors for phones, servers, computers, satellites, cars, etc. TSMC manufactures over 90% of the most advanced chips (generally defined as those made using 7nm processes or smaller) and that makes many people in the Western world uncomfortable given the importance of advanced chips and the ever-looming possibility of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan.

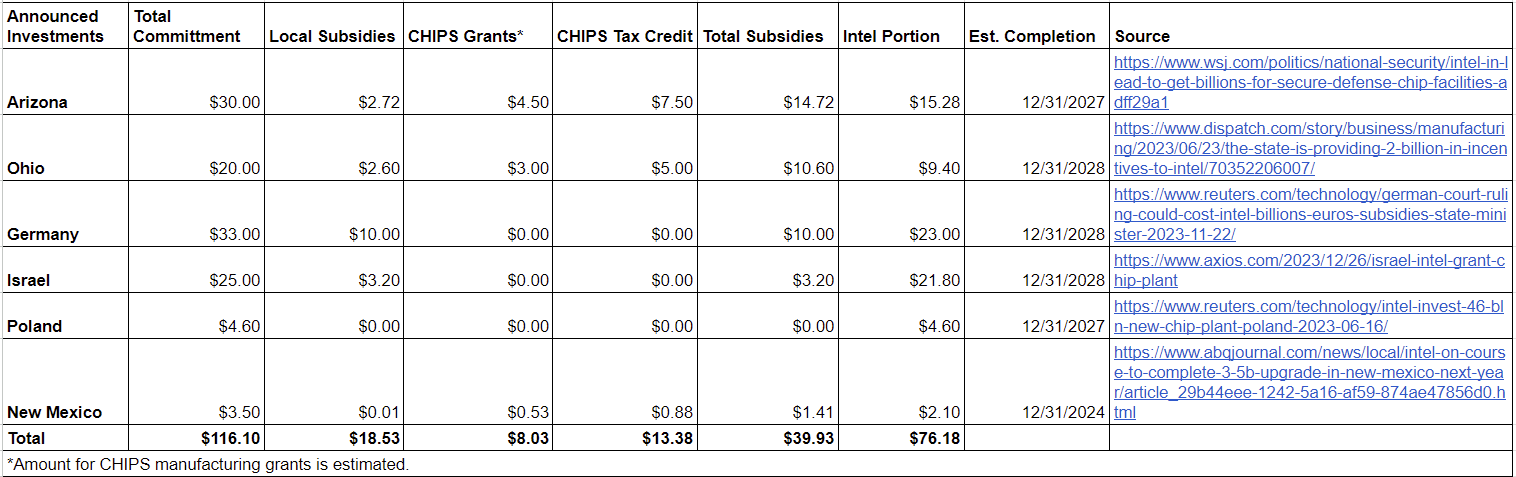

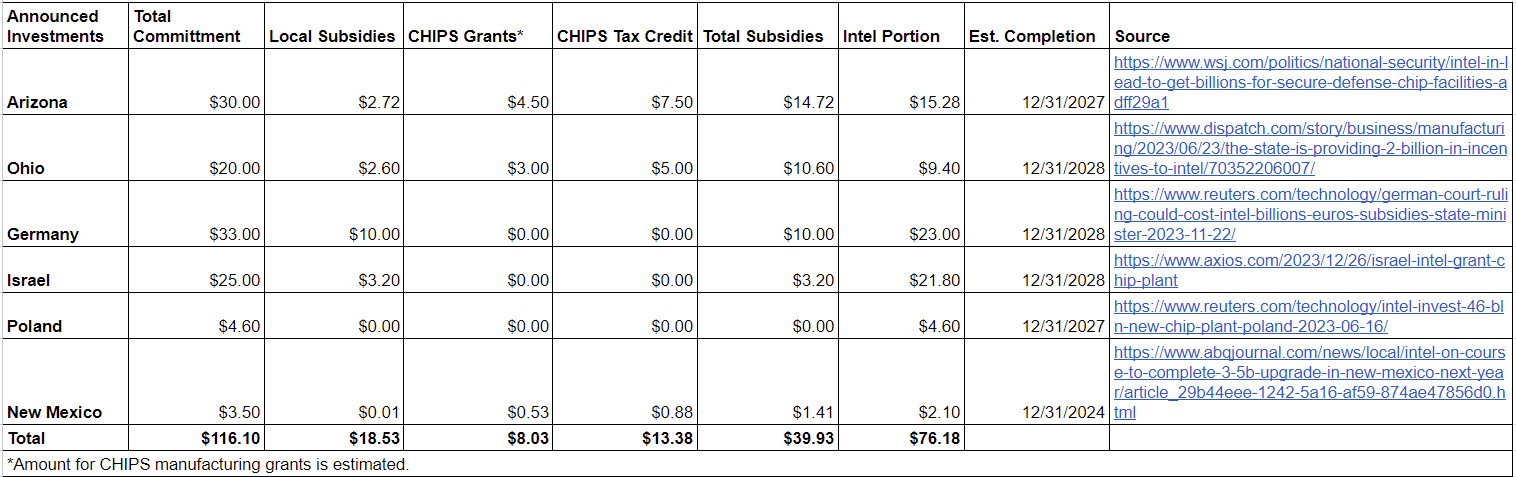

Accordingly, Intel is investing over $116 billion (much of it taxpayer welfare money) to expand its chip fabs and build new ones in the US and Europe to reduce the West’s reliance on Taiwanese chips. Yes, as noted, the governments of the US and EU are picking up the tab for a lot of that CapEx. Below is a table showing Intel’s announced fab investments and a breakdown of how much of each investment we estimate will be subsidized by federal and local governments:

As you can see, roughly a third of the cost of Intel’s planned capacity expansion will be paid for by government subsidies (ie, people’s hard-earned tax dollars). This should reduce Intel’s cost of manufacturing chips and hopefully help make the company more cost-competitive with Asian-based foundries (for reference, TSMC is planning to charge about 30% more for chips made in its US fabs currently under construction).

The long-term bull case for IFS is still well intact. In the fourth quarter, Intel announced that it had signed contracts worth over $10bb in lifetime deal value for the foundry division, more than doubling from the $4bb in contracts announced previously. This is great momentum but the fab business is still a tiny portion (<2%) of Intel’s $50bb in total annual revenue. The process of winning foundry contracts is lengthy and arduous, and the time it takes for those contracts to materialize into revenue takes longer still. However, we are confident that Intel has the technical and financial wherewithal to grow to become a leading global foundry that could rival TSMC.

Once this foundry revenue starts to kick in, the investment case for the company quickly gets exciting. Consider this model: the total foundry market was about $150bb in 2023 with the lion’s share (about 46%) of that going to TSMC. The foundry market is predicted to grow to about $240bb in revenue over the next five or six years, and if Intel could capture, say, 40% of that market (admittedly a big assumption), that translates into about $96bb in incremental revenue for Intel. Assuming Intel could achieve 30% operating margins (for reference, TSMC has a 46% operating margin, and Global Foundries (GFS) has a 16% operating margin), we are talking about $27bb in operating profits for Intel’s foundry division by the year 2029. If we put a 15 price/profits ratio on that (TSMC currently trades at just over 16x operating profits), we are looking at about $410bb in additional market cap just for IFS (or roughly 2.2x Intel’s current market cap).

Intel is holding its Foundry Day on February 21st and we are excited to learn more about the company’s plans for the future of IFS.

2. Process Leadership

Intel is now in the final year of its ambitious “Five-Nodes-In-Four-Years” plan that CEO Pat Gelsinger set out when he returned to the company in 2021. Chips produced using the final node — what Intel calls its 18A node (meaning 18 angstroms or 1.8 nanometers) — are already being manufactured and are set for full commercial production in the back half of 2024. Intel’s 18A process will solidify its lead in terms of the capability to produce the most advanced chips.

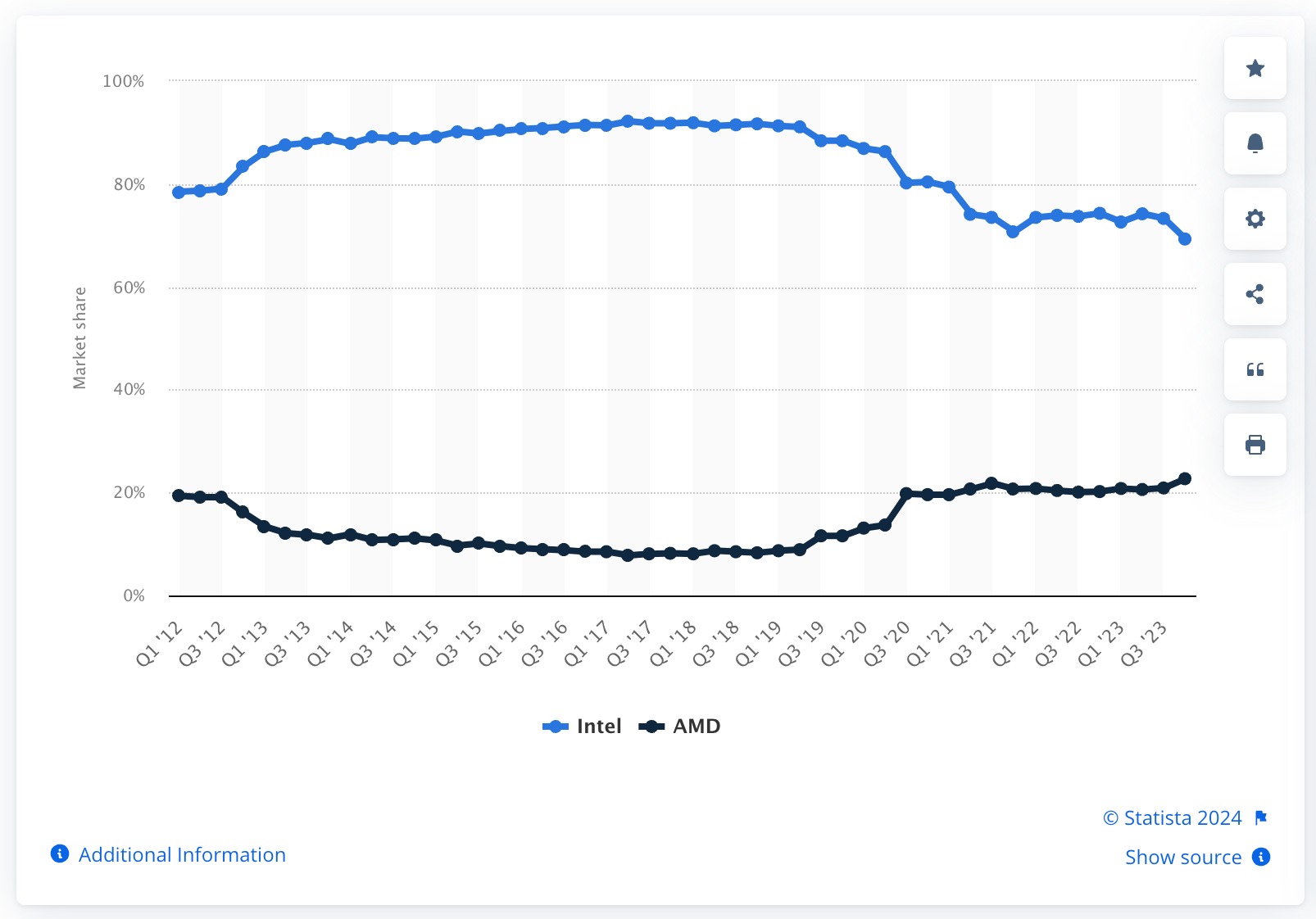

In the chip industry, process leadership ultimately translates into market share gains. This is proven by the fact that Intel started losing market share to AMD in 2017-18 when Intel’s 10nm process fell behind schedule and TSMC’s 10nm process meanwhile was in full production. You can see that in the chart below that shows total x86 processor market share.

However, with Intel’s recent execution of its process roadmap, the company has already started regaining market share in PC CPUs. AMD continues to take share in the server CPU market but we think as Intel continues to roll out new and improved chips, it should be every bit as competitive as AMD in the data center market. We think it’s notable that NVIDIA’s DGX H100 platform ships with Dual Intel Xeon Platinum 8480C Processors (and not AMD chips). Intel will soon start shipping its 5th generation Xeon chips which enable up to 42% higher AI inference performance compared to Intel’s already best-in-class 4th Gen Xeon chips. In our view, Intel simply needs to continue to improve its technology if it is going to continue to grow and fend off competition from AMD, Qualcomm (QCOM), and others who are working on competing CPUs (many of which will be Intel Foundry customers anyway, of course).

So here’s the financial model for Intel’s core chip business: Intel’s three chip divisions (PCs, data center, and networking) made up $51bb in total revenue in 2023, down from a high of $79bb in 2021. We model the PC business growing at a 15% CAGR for the next five years, the server business growing at 13% per year, and the networking line growing at 5% per year. (These assumptions are not terribly aggressive and will look way too low if Intel actually does take serious market share back from AMD in the server CPU market.) If Intel can achieve those growth rates, it will hit a roughly $100bb run rate for its combined chip business in 5 years. Intel’s margins should also improve as it ramps up its most advanced process nodes that it has been pouring money into over the last four years. If operating margins can get back to the 20-25% levels (roughly where they were in 2021), that would produce about $20-$25bb in operating profits in 2029.

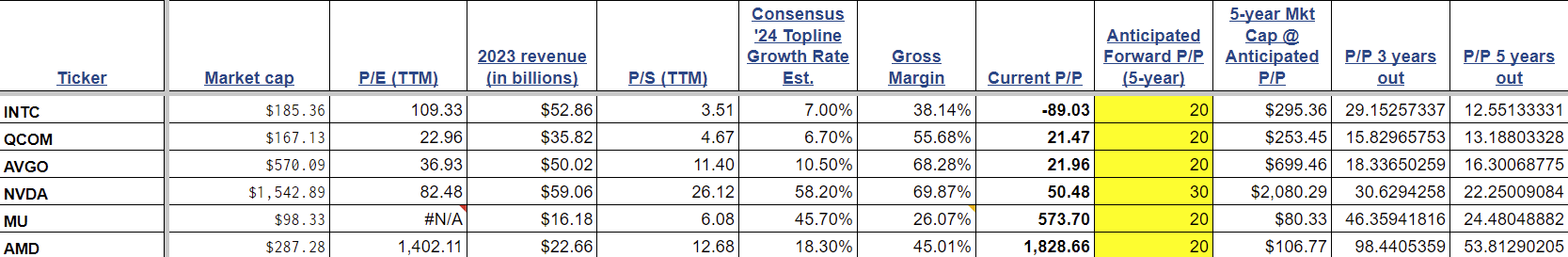

In addition to improving fundamentals, we also expect some multiple expansion if Intel can return to growth and start kicking out some reliable profits again. Intel currently trades at a huge discount to its peers, with the stock currently at only 3.5x TTM sales compared to the average 12.2x price/sales for other large-cap semis. Comp table below:

3. AI Potential

Intel is positioning itself to capitalize on the AI Revolution and it has two key products in our view that could drive substantial growth in the coming decade. First, Intel is already selling its Core Ultra CPU which is specifically designed to handle AI workloads using its integrated neural processing unit (NPU). An NPU is “a specialized processor explicitly designed for executing machine learning algorithms.” Intel’s goal with these chips is to bring “AI everywhere.” These new chips will allow many AI applications to run directly on PCs instead of being run in the cloud as they are currently.

The advantage of AI on the device is four-fold in our view: (1) lower costs (no cloud fees); (2) low latency; (3) better privacy/data protection; and (4) it can be used without an internet connection. Arguably the most important catalyst for making the move to on-device AI is the cost-benefit. Cloud service providers (CSPs) like Amazon, Microsoft, and Google are spending billions of dollars to expand the capabilities of their data centers in order to handle the massive compute workloads required for AI to function. The companies that build AI applications must pay the cloud providers to use their compute power to train and run their AI models. While the massive compute power available in the cloud will still be needed to train AI models, it is probably overkill for most AI inferencing. Many AI applications — like Microsoft CoPilot, Adobe, Zoom, and others (all of which have already announced plans for this edge AI) — can be downloaded and can run on the computer if the computer has integrated AI capabilities. This would save those companies — and ultimately consumers — tons of money since they can avoid incurring continuous cloud service fees.

As these AI applications start to gain mass adoption, it will lead to a massive upgrade cycle in PCs since most people will need a new computer that is powerful enough to handle AI workloads. This could be a major boon for Intel since it is at the forefront of developing PC CPUs designed for AI. However, it is not alone in this market, as AMD and Qualcomm are both developing system-on-a-chip (SoCs) with integrated NPUs. Further, Apple has been building integrated NPUs into its chips since it released the A11 in 2017. In short, Intel will face a lot more of the same competition that it is used to battling against when it comes to selling chips for AI PCs, and the company’s success will likely come down to its technological and price advantages.

The second AI kicker for Intel is its AI accelerator product, Gaudi. Gaudi is essentially Intel’s answer to NVIDIA’s A100/H100 GPUs in that it is a server chip designed specifically for AI processing. Intel is currently selling Gaudi 2 and the chip has already reached a $2bb annual run rate. Intel plans to roll out its upgraded Gaudi 3 accelerator in 2024 which it claims will have 4x the processing power and double the networking bandwidth. Third-party reports indicate that the Guadi 2 is a credible alternative to NVIDIA’s H100 except that it lacks the powerful software ecosystem (known as CUDA) that makes NVIDIA so good and useful.

As AI continues to gain steam, the demand for GPUs and GPU-type chips is increasing exponentially. NVIDIA grew revenues more than double this fiscal year and should grow another 60% next fiscal year. NVIDIA has made clear that it is supply-limited and is working with TSMC and others (potentially IFS) to increase the supply of GPUs to meet the growing demand. Both Intel and AMD are racing to catch up to NVIDIA’s clear lead in the AI computing market, and we expect more competition for NVIDIA chips in the years to come, including from the giant customers of the NVIDIA chips like Google, Microsoft, Meta, etc. But as long as the AI boom continues, we expect there will be plenty of demand for AI accelerators beyond just the top-of-the-line chips from NVIDIA which sell for anywhere from $20,000 to $40,000 per chip. As Intel continues to improve its Gaudi chips and develop its associated software ecosystem, we expect to see Intel start to regain its footing in the data center chip market.

Our biggest concern with Gaudi is that as of the third quarter, Gaudi was still being manufactured by TSMC on its 7nm production node. Intel’s own 7nm process node is now in full production so perhaps Intel can manufacture the Gaudi chips itself. In any case, it is clear that the worldwide supply of advanced chipmaking for server AI chips is limited and that won’t change anytime soon. But we think NVIDIA’s current near-monopoly on AI chips for data centers is probably close to peaking and Intel, AMD, and others including the big tech companies themselves (it’s probably worth reading The Great Semiconductor Shift if you haven’t already) will start to offer more credible alternatives to the NVIDIA platform.

4. Sum of the Parts.

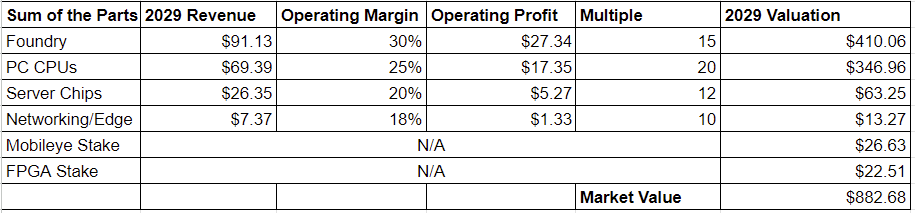

Intel obviously has a lot of moving pieces, and a somewhat useful way to value a company like Intel is with a “sum of the parts” analysis. In addition to its three major chip businesses and its new foundry business, Intel also holds an 88% stake in Mobileye (MBLY) — a maker of LiDAR and other advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS). Further, Intel announced last fall that it would be spinning out its field programmable gate array (FPGA) division sometime in the next two years. The FPGA division is partly the result of Intel’s $16.7bb acquisition of Altera in 2015. Accordingly, we modeled out the future value of each of Intel’s component businesses to see what the company could be worth in five years if everything went well. Our model below shows Intel with a fair value of just over $882bb in 2029 or approximately $208/share (assuming no dilution).

We model the assumptions described in the sections above for the foundry business and core chip business. We model Intel’s relatively small Networking/Edge business growing about 5% per year. We do not attribute much gain to the Mobileye stake (assuming 3% annual growth from the present valuation), and we see the FPGA business coming public at roughly a $20bb valuation (or 6.6x our 2023 sales estimate). The FPGA business is cyclical and we model 3% compounded growth in Intel’s FPGA stake once the division comes public in 2025.

It’s clear that Intel has a lot of levers it can pull to increase shareholder value, and we see lots of potential upside over the next five years if Intel can get a few things to go its way. The PC business looks promising in the near term (33% YoY growth last quarter), but Intel needs its foundry business to get cranking to really get the stock going. That said, Intel’s decision to start manufacturing chips for other companies is a very long-term bet (remember Intel’s $120bb in new/upgraded fabs don’t come online until 2027 for the most part), and it is understandable that the company is not seeing much incremental revenue growth from that business segment just yet.

5. Conclusion.

We like the risk/reward setup for Intel for the long term. That said, the stock had a big run in 2023 (up over 90%) and could have some near-term weakness given the poor guidance for Q1. We want to give this stock some time before we buy more given that we bought it a few times when it fell to around $25. That said, we are still believers in the long-term bull case for Intel and it is one of the only semiconductor stocks that actually grew in Q4 and will grow Q1’24 and every quarter thereafter for the rest of 2024.