Revolution Investing analysis: This ain’t your grandaddy’s banking system

I would like to address two topics that you’ve been emailing me about. First, I appreciate being appreciated and I appreciate everyone who reached out about my re-iteration of our Apollo position last week, after which the stock fell another 10% . Since we’ve made so much money off the name I know some of you are getting antsy to take profits. And yes, I do think that with this stock now down nearly 50% since we added it to the portfolio, that it’s probably time to trim back some of the exposure, even as I think Apollo still has more downside ahead. Just look at what happened with competitor DeVry DV on Monday:

DeVry Inc. (DV) forecast downbeat results for its fiscal fourth quarter and said it plans to cut its workforce, as the for-profit educator said higher-than-anticipated operating costs and continued weakness in student enrollment continued to weaken its results.

Shares sank 20% to $22 after hours Monday.

Apollo is down after-hours too and I expect it to be a nasty couple weeks for the stock. And in the longer run, as I’ve said from the beginning, without continuing Federal largess this one’s a goner.

Since I added Morgan Stanley MS as a short last week the stock has sunk about 10% in a straight line (our other new financial short, J.P. Morgan JPM is down about 2%). I’ve been getting lots of emails already asking if it’s time to cover and take the trading gains, especially from some of you who used puts and are sitting on big gains right now. Every Friday on TradingWithCody.com (a service not affiliated with MarketWatch) I rate my positions from a 1 to a 10, or more scientifically ‘Bail out now!’ to ‘Sell the farm, buy this instead’. I have MS and JPM shorts rated an 8, and I thought you should know why I’m not even close to covering.

There’s an archaic banking saying: “3-6-3”. (I can almost see my old-school banker mentors, including 95-year old local banking legend, Johnson Stearns, smiling right now.) The first two are rates that banks would pay depositors for capital and what they would lend it out, respectively (3%, 6%). The last 3 isfor 3 P.M., or the time you can expect the work day to be done and hit the links. That’s the way banking was for about 70 years, a simple, regional, noncompetitive business, that wasn’t terribly profitable but provided a pretty decent living to pretty decently large number of people.

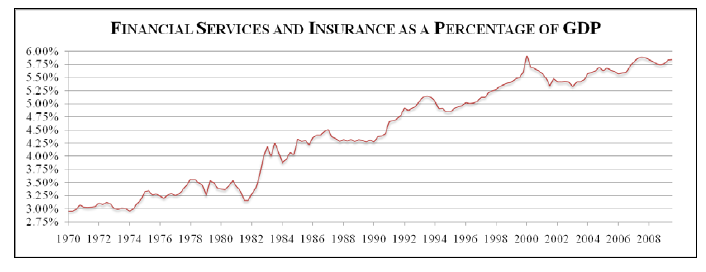

I’m not going to point to the repeal of Glass-Steagall or the Commodity Futures Modernization Act or the Community Reinvestement Act as an inflection point, the influences banks have over policy and the economy had been growing steadily even without regulatory blessing. Check out this chart from the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission:

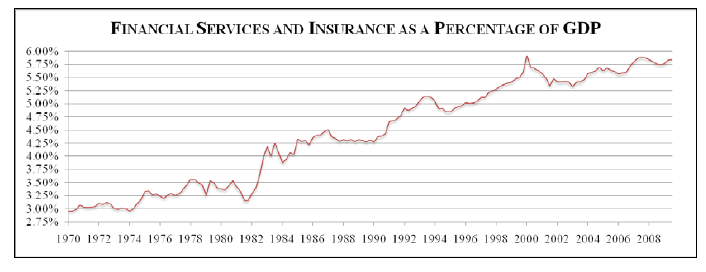

And for proof the trend is really multi-century, look at this chart from the Kauffman Foundation and my friend Paul Kedrosky:

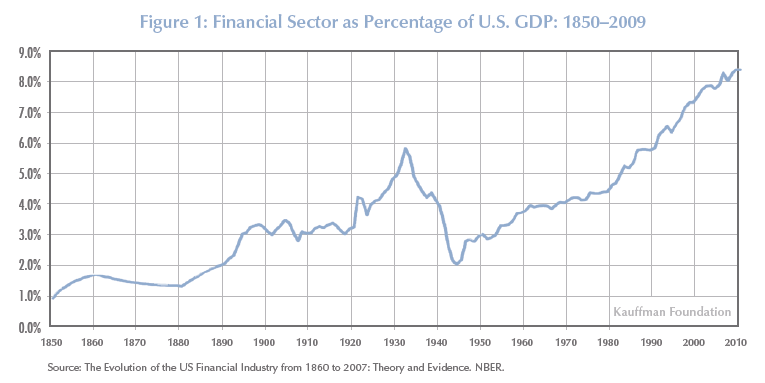

That’s the obvious part, that there’s been huge, long-run growth of the financial sector, punctuated by crises and periods of tremendous boom. But you need to look at this graph from Reuters to really grasp the recent growth rates of what I’m talking about:

If you’re an investor there are two things that should terrify you as an investor. The first is that the nominal outstanding amount of financial debt is actually greater than nominal GDP. When pundits talk about debt-to-GDP of indebted nations and the burden of public employees, they always talk about a ratio of over 100% and how that is the beginning of the end. Why would it be any different for private sector financial companies? Over the last two decades they have become increasingly reliant on the kindness of strangers to lend them money to acquire other banks. The second is that the rate of growth of financial sector debt has been rising ever increasingly over the past two decades. That would be totally unsustainable under normal circumstances, and really, really immediately unsustainable with such anemic global growth. Just so you don’t think this is just a U.S. problem look at this graph from the Bank of International Settlements (they put out awesome reports that no one reads):

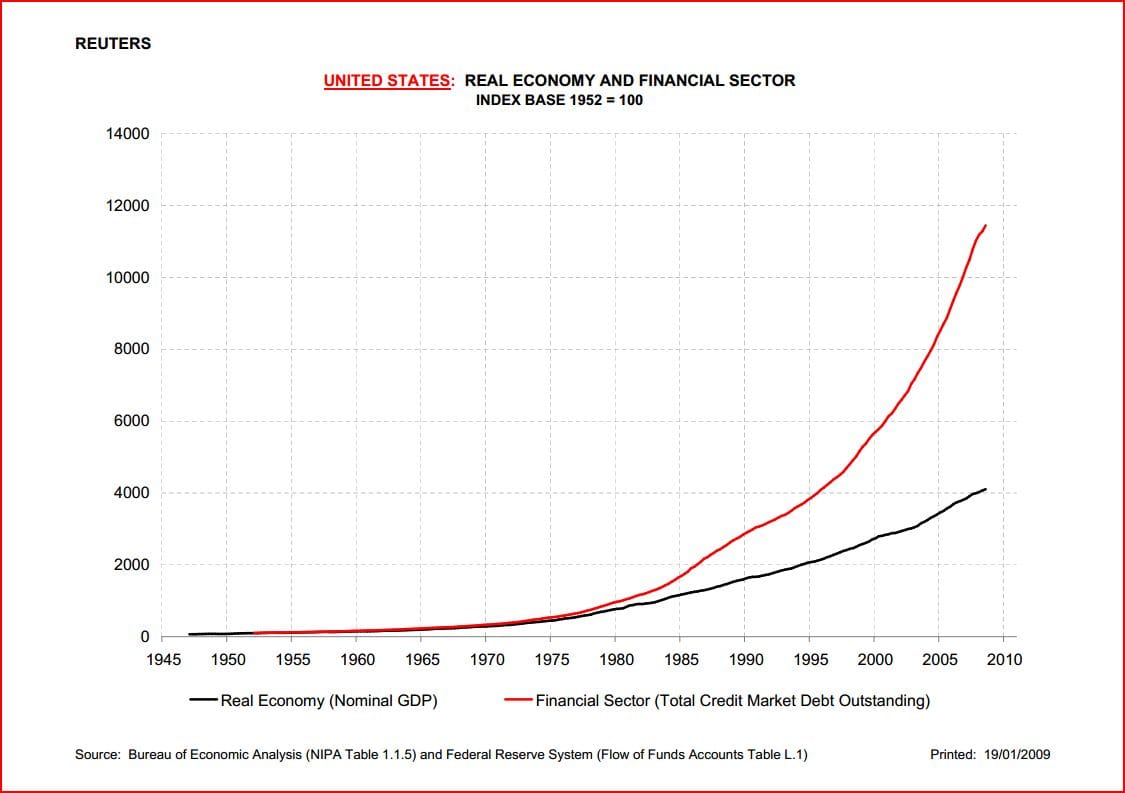

The financial crisis was just a hiccup, look at the percentage of the economy that the Commerce Department puts financial activities at:

Simply put 8.4% of the economy is dedicated to the allocation of capital, not building a better iphone or car, not extracting minerals or making food. That’s unsustainable and un-reflected in the price of banking stocks. Right now the expectations of banks for the long-term are collapsing, and they’re about to return to the long-run profitability, which looks a lot more like banker with a 3 P.M. tee-time at the country club than masters of the universe buying compounds on St. Barths.

Look at this chart from 13 Bankers:

J.P. Morgan has grown largely by acquisition, gobbling up regional banks and money center powerhouses alike (lots of New Yorkers still have their Chemical Bank paraphernalia). But their enormous market cap is supported by about twenty different unsustainable revenue streams. Let’s pick on just one, overdraft fees. The Fed says that total banking overdraft fees were around $30 billion in 2011. J.P. Morgan has a nice $1.12 billion piece of that. Even if they can figure out another way to charge their customers, that shell game is going to take time, and JPM says that the new debit interchanges rules will hit them to the tune of $600M in profit this year. I think it’s going to be more and they don’t have the flexibility right now to devise new profit centers when others are declining.

The immediate situation for Morgan Stanley is even more dire. As I hinted at last week, they have enormous capital investment in their commodities trading business, which is all but going away. In what reeks of desperation over the past quarter, they increased how much trading risk they took on, the only one of the eight major banks to do so, but revenues actually declined. And Morgan Stanley is actively shopping its vast, and immensely profitable, physical commodities business, to satisfy regulators and the ratings agencies. And the one bright spot, the wealth management business? MS can’t even agree with their JV partner Citi what it’s worth. Over time I expect Morgan Stanley to shrink to the size of a respected but small investment bank, like a Lazard. That is if they don’t go up in smoke like a Bear Stearns, something I think is a distinct possibility.